It worked better for Pontiac.

The now-iconic black and gold paint scheme made famous by the ’77 Trans-Am that Burt Reynolds drove into automotive history in Smokey and the Bandit failed to work the same magic on the first GM production car that got the same look.

The ’75 Cosworth Vega.

Probably because under the striking paint job, it was still a Vega – the car that almost doomed General Motors due to its oil-thirsty engine that burned almost as much lubricant as gasoline due to ill-conceived (or rather, ill-manufactured) 2.3 liter aluminum block engines without cylinder liners.

A new casting process was meant to eliminate the need for liners, reducing manufacturing costs but ended up costing Vega owners plenty.

The “tallest, smallest” engine – so named for its long stroke – was prone to horrendous vibration and running hot, due to its siamesed cylinder bores, which made it more vulnerable to overheating, both deficiencies resulting in sealing problems between the aluminum block and the cast iron cylinder head.

Differential heating would warp the dissimilar surfaces; coolant would then leak into the cylinders, scuffing the “diamond cast” machine-finished surface, which quickly resulted in catastrophic wear and horrendous oil consumption.

GM tried to mask the vibration problem by fitting the Vega with extra-flexible rubber engine mounts that allowed the engine to dance under the hood without transmitting the movement to the car’s occupants, in the cabin – but the underlying problems remained, including a just-barely-adequate cooling system that became inadequate when it ran even slightly low – which would happen when it boiled over – cue overheating and then sealing and then cylinder scuffing and then oil-burning.

Plus shoddy valve stem seals and a backfire-tending carburetor that sometimes triggered fires downstream in the exhaust system.

It made the Pinto seem like a Rolex.

But wait, there’s more!

Early Vegas also were afflicted with an idle-stop solenoid bracket that had a tendency to work loose, jamming the throttle open. Chevy advised owners to “turn off the ignition and apply the brakes” in the event this happened.

The Vega’s problems weren’t just under the hood, either. The rear axle was prone to inadvertent disassembly while the car was moving; the “electrophoretic” anti-corrosion treatment dip applied to the body at the factory was not applied uniformly, resulting in early rusting of untreated areas, especially in the cowl area and around the front fenders.

Routine alignments could not be performed because of seized fittings that necessitated cutting off the affected components with an acetylene torch and replacing them before adjusting them. The area around the base of the car’s windshield often rusted out so severely that the windshield was no longer securely held in place and would fall into the car.

Six of seven early Vegas – which first became available in 1970 as ’71 models – were recalled for one reason or another and often several. GM had to replace more engines under warranty almost as quickly as the factory engines went through a case of oil.

John DeLorean – who oversaw the early years of the Vega’s development as Chevy’s general manager, blamed rushed development and rushed assembly for most of the car’s (and buyers’) woes. The Vega was hashed together over the course of just 24 months without – according to DeLorean – adequate time to fully test the essential soundness of the design.

One test mule reportedly came apart – literally – while being evaluated on GM’s proving grounds in Michigan. But instead of halting the production schedule to find out why this happened – and fix it – management greenlit production. The company was reportedly desperate to get the car into showrooms for the 1971 model year, no matter what.

And then “what” happened.

“While I was convinced that we were doing our best with the car that was given to us, I was called upon by the corporation to tout the car far beyond my personal convictions about it,” he told J. Patrick Wright, author of On a Clear Day You Can See General Motors – which was published in 1979. By then, DeLorean was working on his own – on what would prove to be another Doomed car, the infamous stainless steel-bodied, gullwinged DeLorean DMC coupe of Back to the Future movie fame.

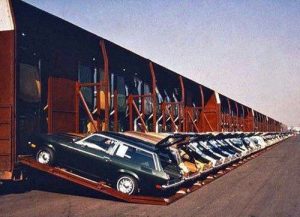

When Vega production began in 1970, it was on a hurried-up schedule, too. The Lordstown, Ohio assembly plant was initially chucking out 100 new Vegas per hour, twice the usual volume. Much of the line was automated, using Unimate industrial robots to perform 95 percent of the 3,900 welds necessary to put the bodies together. But the work that still had to be done by hand was double-speeded such that a task that had previously been allotted 1 minute to perform was now supposed to be done in 36 seconds.

Predictably, build quality was spotty.

As was paint quality, which was below the usual standard because the spray booths were expected to finish cars much faster than they had been designed to handle, leading to runs and sags and orange peeling paint jobs that had to be redone either at the factory or the dealership.

Though initially well-received, the Vega quickly became GM’s biggest and most publicly embarrassing fail since the first-generation Corvair, a car that was far less lemony in terms of its basic soundness. Unlike the Vega, the Corvair wasn’t poorly built relative to others cars of its time and its bad reputation for evil handling wasn’t so much the car’s fault as the fault of drivers who failed to heed the factory tire inflation recommendations and then drove the car beyond their capabilities.

Cars magazine summed up the situation with the Vega up as follows: “Tests which should have been done at the proving grounds were performed by customers, necessitating numerous piecemeal fixes by dealers. Chevrolet’s ‘bright star’ received an enduring black eye despite a continuing development program which eventually alleviated most of these initial shortcomings.”

That sets the scene for the Cosworth Vega, which – so it was hoped – would rehab the Vega’s by-then horrendous reputation by showcasing technology that not even the Corvette was available with, such as electronic port fuel injection. The Cosworth Vega was the first GM production car to come standard with it.

Also the black and gold paint scheme – with matching gold-anodized alloy wheels (years before the Trans-Am would offer such) and “engine-turned” dash facing, styling touches that would be iconic a couple of years later when they were used to create the “Bandit” Trans-Am.

The Cosworth Vega also had things no “Bandit” Trans-Am ever got, including 9,500 RPM capability (with a 7,000 RPM redline for the production engine) and a higher (122 MPH) top speed. The “Bandit” Trans-Am’s 400 cubic inch V8 engine redlined just over 5,000 RPM and its top speed was gearing-limited to about 118 MPH.

But the “Bandit” was a Trans-Am and didn’t have the legacy problems that beset the Cosworth Vega before the first one was offered for sale in ’75. Still, there is no denying it was a revolutionary car for its time and had GM built a Vega that was more like the Cosworth Vega back in ’71, the stars might have aligned better for this ill-fated attempt to repair what was probably already beyond repair.

Development work actually began shortly after the ’71 launch of the regular Vega. DeLorean sent engineer Calvin Wade to England, to commune with British engineers at Cosworth, whose specialty was (and is) the development of high-airflow/high-revving engines, chiefly for F1 racing.

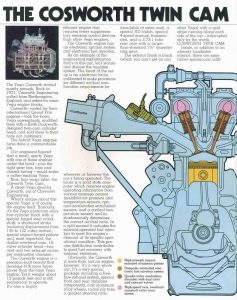

GM would collaborate with Cosworth to develop a new high-performance street engine based on race car engine design, in particular the dual overhead cam cylinder head bolted to the standard Vega engine block. This time, there would be no aluminum block/iron head mismatch and built-in sealing problems. While the block was more or less stock, it was fitted with high-strength/lightweight forged aluminum pistons to reduce the mass of the reciprocating assembly, so as to enhance the high-RPM capability. The crank was also upgraded to heat-treated forged (rather than cast) steel while the Cosworth-designed head got sintered iron valve seats.

A beautiful stainless steel header snaked backward toward the cowl, where it fed into (initially) a dual outlet exhaust. The engine – with its aluminum rather than cast iron cylinder head – shaved some 60 pounds off the Vega’s nose, resulting in a curb weight of just 2,760 pounds.

The car’s serious demeanor was enhanced by the absence of amenities such as air conditioning and power steering – but the real eye-popper was the Bendix port-fuel injection (PFI) system that fed the mighty-mouse engine. This was a leap ahead of the throttle body (TBI) systems that began to gradually replace mechanical carburetors beginning in the early-mid 1980s. TBI systems were functionally very similar to carburetors in that they used a single throttle body – which sprayed fuel into a common intake plenum, or manifold, the fuel and air then sucked into the engine’s intake ports. PFI uses an individual injector for each of the engine’s cylinders; this allows much more precise tailoring of the amount of fuel being injected, a boon for both power and economy as well as lower emissions – which GM and other car companies were faced with having to deal with in a big way by 1975.

To get by the EPA’s new strictures, almost every new car made for ’75 had to have a catalytic converter – essentially a chemical exhaust scrubber – and the still-carburetor-fed engines of the time had to be tuned to run very lean, which made them run not very well. It also had a crippling effect on horsepower and performance.

The ’77 “Bandit” Trans-Am looked fast but its 6.6 liter 400 cubic inch V8 only summoned 200 horsepower, which wasn’t enough to lug the 3,800 pound Trans-Am to 60 more quickly than about 7 seconds.

Thanks to its free-flowing Cosworth head, its Bendix EFI system – and not having to lug around 3,800 pounds – the Cosworth Vega was nearly as quick to 60 and slightly faster on top. Its freer-breathing, much-freer-revving, shorter-stroke 122 cubic inch engine may have only developed 110 horsepower in production tune but development mules were making 170-260 using the stock block and even 110 hp was proportionately impressive for an engine less than half the size of the Trans-Am’s 400 cubic inch engine.

But it was also an expensive engine, accounting for much of the cost of the car – which at $5,918 asking MSRP was nearly the same asking price of a new Corvette.

The Bendix EFI system included multiple sensors, in addition to multiple injectors and a computer – the ECU, or Electronic Control Unit – to run the works. It was very elaborate, very expensive tech for 1975.

And it was hard to convince people to pay for it in a Vega, rather than a Corvette.

Even so, the car press loved it. Motor Trend enthused that “it goes like the proverbial bat out of Carlsburg Caverns,” particularly praising the engine’s 7,000 RPM capability. Car and Driver described it as a “taut-muscled GT coupe to devastate the smugness of BMW 2002tii’s and Alfa GTVs.”

But the price was just too high – and the reputation’s stink just couldn’t be dissipated.

After a poor reception in its debut year, Chevy tried further enticements, such as a new standard five-speed (overdrive) manual transmission – replacing the ’75’s four speed without OD (no automatic was ever offered due to the engine’s high-RPM, race-bred character) and the availability of a SkyRoof and 8-track tape player/AM/FM stereo combo.

AC, however, was still off the table. Also power brakes – and windows. It was as close to a factory racer as you could buy that year – assuming you could afford to buy it. Chevy even touted its cost: One Vega for the price of two.

It wasn’t the ticket for sales success.

Over the course of its two-year production life, just 3,508 cars were sold – falling well shy of the initially intended 4,000 examples Chevy had planned to sell. GM would not offer EFI in a production car for almost another decade – and then in the Corvette, in the form of what was marketed as Tuned Port Injection (TPI) beginning in 1984. By then, people were willing to pay for it, provided it was in a Corvette.

The tragic thing about the Cosworth is that it was a good-looking, good-handling, extremely sophisticated car that probably would have done well – if it hadn’t been a Vega.

And the Vega didn’t have to be the Hindenburg-level disaster it turned out to be for all concerned, including GM – which to this day hasn’t recovered from the damage to its reputation incurred by the slipshod design and rushed production of the ’71 Vega.

As of 2021, General Motors – all of it – sells fewer cars than Chevrolet, by itself, sold in 1970. Largely because it drove away half of its market by trying to sell people cars like the early Vegas.

. . .

Cosworth Vega Trivia:

-

- Cosworth Vega engines were hand-assembled on a special line by teams of 2-3 master technicians at the Tonowanda engine assembly plant in New York. A number of completed engines – perhaps as many as 500 – were ultimately scrapped after the car was cancelled.

- GM designer Bill Mitchell, who styled the 1970 Camaro, was heavily involved the styling of the original 1971 Vega, which borrows heavily from the Camaro’s overall themes.

- Race versions of the Cosworth engines had dry sump oiling systems, higher compression ratios and Lucas mechanical fuel injection but were otherwise very similar to the production street car versions.

- During pre-production testing, the Cosworth engine held together when spun to 9,400 RPM and subjected to 500 hours of operation at full load.

- While first-year Cosworth Vegas are all finished with black and gold exteriors, second-year Cosworths were available in a variety of palettes, including Antique White, Dark Green Metallic, Buckskin, Firethorn Red Metallic, Medium Orange, Medium Saddle Mteallic and Dark Blue Metallic. ’76 models also have different-design tail lights and grill as well as the five-speed overdrive manual transmission that was not offered in ’75. These last year Cosworths are also the rarest of the breed, with 1,447 examples made vs. 2,061 in ’75.

- Both years came with serialized plaques, the gold-faced engine-turned dash with full gauges (including an 8,000 RPM tachometer) and Camaro-style steering wheel with special badging.

- The last Cosworth Vega delivered to a dealer was painted Medium Saddle Metallic and delivered to a dealership in Cleveland, Ohio.

- The very first Cosworth – serial number 0001 – is currently part of the GM Heritage Collection and occasionally displayed. It has a see-through plexiglass hood to showcase the Cosworth engine underneath.

- The Vega, itself, survived for one more year – but was cancelled after the 1977 model year. Its replacement, the Monza, was heavily based on the Vega but restyled to avoid any comparisons. It was cancelled after the 1980 model year.

- Cosworth Vega engines were hand-assembled on a special line by teams of 2-3 master technicians at the Tonowanda engine assembly plant in New York. A number of completed engines – perhaps as many as 500 – were ultimately scrapped after the car was cancelled.

Excerpted from the forthcoming (soon!) book, Doomed.

. . . .

Got a question about cars, Libertarian politics – or anything else? Click on the “ask Eric” link and send ’em in!

If you like what you’ve found here please consider supporting EPautos.

We depend on you to keep the wheels turning!

Our donate button is here.

If you prefer not to use PayPal, our mailing address is:

EPautos

721 Hummingbird Lane SE

Copper Hill, VA 24079

PS: Get an EPautos magnet or sticker or coaster in return for a $20 or more one-time donation or a $10 or more monthly recurring donation. (Please be sure to tell us you want a magnet or sticker or coaster – and also, provide an address, so we know where to mail the thing!)

My eBook about car buying (new and used) is also available for your favorite price – free! Click here. If that fails, email me at EPeters952@yahoo.com and I will send you a copy directly!

Forget all this crap. Here’s the real story.

The Chevrolet Cosworth Vega was decades ahead of its time

By Robert Spinello

The Cosworth Vega had more technology under the hood than any American car by two decades. RPO Z/09: All-aluminum construction, 2-Liters, 16-valves, dual overhead camshafts, electronic fuel injection, stainless steel exhaust header, aluminum alloy diecast cylinder block with silicon bore surfaces, iron-plated forged aluminum pistons, magnafluxed connecting rods, forged crankshaft w/ tuft riding heat treatment, 356 aluminum alloy cylinder head with sintered-iron valve seats and cast-alloy valve guides.

The Cosworth Vega engine is a direct derivative of the Chevy-Cosworth EA Formula racing engine. Although it has been widely thought of by the general public as a souped up Vega engine, it is in truth a de-tuned EA racing engine. It lacks the EA’s dry sump lubricating system (neither necessary nor desirable for passenger car application), has a lower compression ratio and different valve timing and uses Bendix electronic fuel injection in place of the Lucas mechanical injection, but bore, stroke and valve sizes are identical. The Bendix injection is more sophisticated than the Lucas since it has to cope with a wider range of operating conditions as well as emission controls. In 1975-’76 an all aluminum 2.0 liter twin cam engine with 4-valves per cylinder and electronic fuel injection was only found under the hood of the limited production Cosworth Vega. Today. 2.0 liter twin cam, 16-valve engines are widely used powering Toyotas to Audis to Cadillacs, and for good reason. The 4 valves per cylinder twin cam design pollutes less than any other configuration (the only engine in 1975 certified for all 50 states) while the 2.0 liter size produces ample, efficient power with less vibration and better fuel economy than larger 4 or 6 cylinder engines.

Veteran engineers Ed Cole and John DeLorean running General Motors and Chevrolet respectively in the early 1970s had vision looking forward, not back. In 1970, before the Vega 2300 was introduced to the public, DeLorean supplied Cosworth Engineering, Northampton England (176 wins in Formula 1 ranked third under Ferrari and Mercedes) with Vega aluminum engine blocks. They built the 260-hp Chevy-Cosworth EA Formula racing engine with there own aluminum 16-valve twin-cam cylinder head. Easter 1972, Ed Cole test drove two Vega prototypes, The Chevy-built Cosworth twin-cam road version and an aluminum small block V8. Cole chose the Cosworth stating, “it’s the nicest four cylinder I ever drove.” and DeLorean authorized production with the purpose of enhancing Chevrolet’s performance image while drawing attention to the Vega lineup, their best selling small car. With a low priority assigned to the program and a five year gestation period, Cole and DeLorean had retired from General Motors by the time the Cosworth Vega Twin-Cam was introduced in March, 1975. The engine was tested 500 hours at full output, twice the normal time and a clutch burst test at 9,500 rpm incurred no damage to the engine or clutch. 5,000 were hand built and signed by each engine’s main builder with no time or cost restraints and like Cosworth’s racing version, with durable forged components. 3,508 cars were assembled together in batches at Lordstown over 17 months with a new torque-arm rear suspension (to control rear-wheel hop), unique suspension tuning, British-made gold painted alloy wheels and gold body pinstriping each assigned a consecutive build number stamped onto a gold plated brass dash plaque affixed to a gold engine-turned dash bezel. Road test magazine had said, “…not even Ferrari can offer that.”

The production Cosworth Vega engine developed 110-bhp with an 8.5 compression ratio, a pulse-air emissions system, a catalytic converter and Bendix electronic fuel injection designed specifically for the road version. Car and Driver clocked the Cosworth Vega in October 1975 at 0-60 in 8.7 seconds with a top speed of 107 mph. Any car meeting 1975 emission standards able to accelerate to 60-mph in under 10 seconds was considered fast. The 110-bhp 122 cu ’75 Cosworth Vega was tested faster 0-60 than the 155-hp 140 cu. in Yenko Stinger II turbo (9.0 sec), 245-hp 454 cu in ’74 Chevelle (10.5 sec) and faster than its four cylinder foreign competition including the 98-hp 122 cu in ’75 BMW 2002 (10.7 sec) at the same MSRP. Tougher still emission standards for 1977 required a third 50,000 mile certification test. Chevrolet ended the program writing off 1,000 of the engines for 10 million dollars. The majority of the 3,508 cars have survived. Too bad Cole and DeLorean, the car or the engine itself doesn’t get a mention foretelling nearly half a century earlier what powerplant would be found in your average American or foreign car, an all-aluminum 2.0 liter twin-cam with 4-valves per cylinder and electronic fuel injection. I’m talking about historical significance here.

and how does it run modified with 216-hp?

Clover,

“How it runs modified” is irrelevant – as regards how it ran in factory stock condition. In factory stock condition, my ’76 Trans-Am’s 455 made 200 horsepower. It now makes close to twice that . . . modified. It says nothing about the car as it came, other than what it is capable of… modified.

And: A stock ’76 Trans-Am is still a Trans-Am. A Vega – no matter how much modified – will always be a Vega.

“Probably because under the striking paint job, it was still a Vega – the car that almost doomed General Motors due to its oil-thirsty engine that burned almost as much lubricant as gasoline due to ill-conceived (or rather, ill-manufactured) 2.3 liter aluminum block engines without cylinder liners.”

Both my 72GT and my 77GT never burned oil, and don’t to this day. So if it had been a ill-conceived engine or ill-manufactured engine, would NOT my cars have been the same? And why mention no cylinder liners, unless it was intended to imply that oil burning was due to no liners?

This is not to say that some of the engines didn’t use oil. But in fact, there were no complaints about a fog of blue smoke behind every Vega. So clearly, they didn’t burn oil. More precisely, they lost oil. And the lack of liners was not the cause. Oil was lost through the valve seals. This is an important fact. The engines lacked proper repair when the seals failed.

Why would improper repair happen? Because mechanics would rather sell a new engine for about $1000 than to perform a relatively simple (no engine removal) valve seal replacement for $250. That, and mechanics were reading critiques of this new aluminum engine with NO liners, and that most certainly must be causing some sort of problem, right? Aluminum is a soft metal, everyone know that. But still, no blue smoke out the tail pipe before repair.

As PT Barnum used to say, “There is one born every minute.” Well, maybe every 20 seconds given the size of the population.

Important note: Cosworth’s did not have the same head and valve configuration, so even a layman (a layman willing to spend $6500 on a Cosworth? Really? or just a steep learning curve on every large investment? and therefore, not having $6500 of disposable income) would have a hard time confusing a 2.0L engine with a 2.3L engine. Cosworth’s didn’t lose oil, so there is no comparison that way.

Hi Mark,

The Vega’s problems were numerous and well-documented; even by the slipshod standards of the ’70s, it was a poorly-made car.

The devil is in the details, isn’t it? Oil burning by definition means blue smoke out the tail pipe. Can’t have one without the other. I guess that was overlooked. So, what does that omission mean? The reader will decide.

Hi Mark,

” Oil burning by definition means blue smoke out the tail pipe. ”

Actually, not necessarily. Not visibly, anyhow. Ask around. It is fairly common for some engines to use a lot of oil without a lot of visible smoke. The GM Northstar was one.

As far as the rest: The Vega was built to be cheap and disposable – and was. It also had more than its share of defects, even for an era when such were far more widespread than today. This doesn’t mean it was an awful car. But it was far from a great car.

The Vega’s oil burning problem was due to its sleeveless aluminum block. The casting technology had hard particles of some other material in it. So long as they were distributed properly it worked. It’s the kind of thing that works on nicely controlled prototypes but then goes all wrong in high volume production when the speed dials are turned up and the average employees are doing the work.

So no, not all vegas burned oil. Only those that got blocks that were not cast correctly and the hard particles that kept the bores from wearing were distributed properly.

I don’t recall my parents’ Vega burning oil, just leaking it. A lot of it. The oil slick was on the driveway years after the car was gone. I do believe the engine wasn’t a bad oil burner because the next owner repaired the rust, maybe or maybe not fixed the oil leakage, and flipped it. So long as it was fed oil the engine wasn’t going to die.

Eric,

Who would have thought that an article about the Coxworth Vega would generate this much intensity…Quite bizarre!

Robert surely appears to know much about the Chevrolet Vega; the way in which he presents the information might need a bit of tweaking however.

It is safe to say that both Eric and Robert appreciate and are quite fond of the Coxworth!

Now, back to my parasitic draw investigation on my 2004 VW Touareg…

. At $4,900 a copy they would have sold all 5,000 before they built. And that’s exactly what they did if they sat on the floor too long. End of story.

In other words, Robert, they had to cut the price by an enormous (proportionately) sum to get them off the showroom floor. The same technique was used to “sell” the Aztek!

Why can’t you admit the inarguable – that the car was a sales flop – while still admiring the car? Why not at least read the article – which you say you haven’t – before posting dozens of semi-literate diatribes castigating me for writing what you haven’t even read?

If you do, you’ll discover I like the car, too.

Chevrolet Vega 2300—It’s been 50 years Setting the record straight

By Robert Spinello April 24, 2020

General Motors had unlimited resources including $200 million for the Vega program (a billion in today’s money). They didn’t have to settle for an existing engine in an all-new car as Ford did with its German 2000 OHC inline-4 (prone to excessive cam and follower wear) or worse, its British 1600 OHV inline-4, standard equipment in the 1971 Pinto and Capri (with a pitiful 0-60 in 20 sec.)

That’s one reason why the Pinto and and eight other coty nominees didn’t get the Motor Trend 1971 Car of the Year award, the Vega 2300 did. It’s larger 4-cyl. engine provided the torque to handle options most buyers wanted and had decent performance (0-60 in 12.5 sec; top speed of 105 mph). Not to mention the handling characteristics of a sports car. The Fords (and several imports) weren’t even offered initially with automatic transmission or air conditioning. The Vega was capable of sustained long-distance driving in comfort right out of the gate. Motor Trend said, “For the money, no other American car can offer more.”

General Motors and Reynolds Aluminum had been working on a linerless, aluminum engine block as early as the 1950s, The new technology wasn’t ready for Chevy’s aluminum flat-6 or Buick’s aluminum V8 at the start of the 60’s, but was for GM’s aluminum inline-4 by the end of the 60s. The 2300 engine and its die-cast block technology was developed at GM engineering staff long before the program was handed-off to Chevrolet to finalize and bring to production. The technical breakthroughs of the Vega block lie in the die-casting method used to produce it, and in the silicon alloying which provided a compatible bore surface without liners. With a machined weight of 36 pounds, the block weighed 51 pounds less than the cast-iron block in the Chevy II 153 cu. in. inline-4.

Car and Driver 1971 Yearbook: Chevy’s Automated Engine—Make it Cheaper But Make it Work—editor Karl E, Ludvigsen said, “It is possible that Chevy may have equaled its 1955 achievement with its new small-car engine. A power unit astutely planned over the course of a decade, that is, in the strictest sense, a rawboned machine. t’s not a high-revving, high-speed engine; instead, it’s designed for good performance at moderate speeds. Still, it has an overhead camshaft…” ” Now we know what GM’s chairman meant in October, 1968 when he announced that his firm’s new small car would have “a new and different engine, made possible only through important advances in technology.”

Collectible Automobile, April 2000: “The Vega engine was, without a doubt, the most extraordinary part of the car.”

Chevrolet corrected the engine’s potential overheating issue early on with the addition of a retrofitted coolant recovery system, low-coolant warning light and further, with a redesigned head gasket made of stainless steel.

Let’s get real. If the design had proven defective, it would have been scrapped well before the first of two million were sent out to the public. GM scrapped the rotary engine, destined for the 1974 Vega for wear and emissions issues after spending $60 million, but didn’t scrap the Vega 2300 engine. And that speaks volumes. The same linerless block was utilized for the Cosworth’s 270-hp EA racing engine and the hand-built Cosworth Vega Twin-Cam production engine, tested at 9,500 rpm with no damage to the block or its forged components.

When properly finished, hypereutectic-aluminum cylinder bores present a surface to the piston rings that’s roughly equivalent to glass The resulting engine has lower friction, excellent sealing, improved dimensional stability, improved heat dissipation, reduced weight, better recyclability, lower manufacturing cost and higher durability – compared to the traditional aluminum block with cast-iron cylinder liners.

© 2020 Sunnen. All rights reserved.

Motor Trend, September 1974, editor John Lamm said, “incidently, because present problems with overheating and warpage of the Vega engines have been caused by owners driving around with too little coolant, all Vegas will have an instrument panel light warning when coolant is down one quart.”

Non-a/c cars (except Cosworth Twin-Cam) had a two-tube, 12″x12″ radiator that held only 6 quarts but when topped off the cooling system was adequate. But most owners tended not to check the coolant level often enough. In combination with leaking valve-stem seals, the engine would often be low on oil and coolant simultaneously. This caused overheating which distorted the open deck block allowing antifreeze to seep past the head gasket, causing piston scuffing inside the cylinders..

Chevrolet informed the 1.3 million owners that it would repair, at its own expense, any engines damaged by overheating. An owner with a damaged engine had a choice to have the short block replaced with a brand new GM unit or a remanufactured, aftermarket steel-sleeved unit. A coolant recovery system was retrofitted to early cars (factory installed from 1972-on), along with a low coolant warning light (factory installed from mid-1974-on).

Vega owners could have rectified the inevitable oil consumption issue (with reducing the possibility of engine damage and overheating) by having deteriorating valve stem seals replaced, an inexpensive fix, but most owners didn’t have a clue, or a care. A quart of oil was $0.41 in 1972.

Many Vega owners believed and many car “know-it-alls” believe steel sleeves for the Vega 2300 aluminum block solved the engine’s oil consumption issue. It didn’t solve anything. In seven years production of 2,010,547 Vegas, the GM Tonawanda engine plant never sleeved one Vega engine block. For one, silicon is more durable than steel. Silicon is 7 on a scale of 10 in hardness, while steel is 5 on the scale. So why would GM have wasted 20 years of research and development? It wouldn’t have made any sense to substitute steel sleeves for the silicon etched bores because given the facts, there was no advantage in doing so.

The aftermarket supplied re-manufactured, sleeved 2300 partial engines for GM as an easier alternative to honing the silicon etched cylinders and a cheaper alternative to a new linerless block replacement, but utilizing the linerless block was far superior. Adding sleeves took away the advantages of the original design. The steel-sleeved block was just more cost-effective for GM on cars under warranty and more profitable for dealers on cars out of warranty..

Motorology, Tom Mooty (Facebook) said, “IMHO much of the cavitation corrosion that created the need for flanged sleeves that replaced the entire sealing surface at the deck were caused by misinformed owners who recklessly removed and plugged all the vacuum hoses in the belief that they were disabling the emissions controls. In reality they were giving the ignition too much advance and often leaning it out too much, creating damaging detonation. Also, GM specified an unusually tight piston to wall clearance, likely because of the similar rate of thermal expansion between the piston and wall. Unfortunately, too many owners wouldn’t warm them properly before loading the engine enough to get the piston hot and expand it while the cylinder was still surrounded by coolant that was at a lower temperature. That would scuff the pistons prematurely.”

The Vega engine underwent continuous development and was improved annually. Drivability and carburator issues (of which all early 70’s cars suffered) were ironed out over two years. The head gasket failure issue (8% in 1971-’72) was rectified with two revisions to the head gasket, one early on with a switch to one of stainless steel and yet another revision In 1976, along with improved valve seals, reducing oil consumption by 50%, revised engine block cooling slots, and revisions to the water pump and thermostat. The switch to quieter hydraulic valves was probably made because the engine was utilized as standard equipment in the up-scale Olds Starfire for the 1976 model year as well as the Chevy Monza since its introduction the year before. A 5 year/60,000 warranty, the longest ever offered at the time was included with the newly-named “Dura-built 140” engine.

Hypereutectic aluminum cylinders have evolved considerably since the Vega. And while GM led the way with the Vega engine, today Europe and Japan are leading the trend to the linerless aluminum block. OEM’s using the material include Mercedes, Audi, Porsche, BMW, Volvo, VW, Jaguar, Yamaha, and Honda. Manufacturers of power sport vehicles, outboard motors and compressors also use hypereutectic cylinders.

© 2020 Sunnen. All rights reserved.

The Vega’s linerless, aluminum engine block was an automotive engineering milestone for a simply designed engine for General Motors’ otherwise conventional, and least expensive car.

The same engine block with a little help from John DeLorean, inspired the Cosworth EA Formula 1 racing engine and the production of 5,000 all-aluminum 16-valve fuel-injected Cosworth Twin-Cam 4s, “the most sophisticated engine Detroit had ever built”, making the Cosworth Vega Chevrolet’s most exclusive and expensive “passenger car” In 1975-’76, $1,500 within of the price of the 1976 Corvette.

Current market values (Hagerty Valuation), for the best 1976 examples, the Cosworth Vega is worth 700% ($42,500) of its original MSRP ($6,066) which is $19,600 more than the current value of the best 1976 Corvettes at 300% ($22,900) of original MSRP ($7605).

The advanced technology of the Vega engine block and the Cosworth Twin-Cam engine were decades ahead of their time. “Auto experts” should give some credit where it’s due. But they’re too busy praising dated pony cars and overpriced foreign sports cars, including rust-prone 911s, 2.7 liter versions with inferior magnesium engine blocks.

https://www.facebook.com/groups/771348593004210/posts/1663304080475319

Further reading: Chevy Vega Wiki; Chevrolet Vega Engines https://chevyvega.fandom.com/wiki/Chevrolet_Vega#Engines

Doomed? My 1976 Cosworth is worth $42,500 as of May 2021 according to auction and private sales as per Hagerty Valuations. When I bought it in 2012 it was worth $13,000. Doomed? I don’t think so.

Hi Robert,

As a collectible, today – sure, it’s worth a lot of money. But did it succeed when it was available, new? No. It was much too expensive and performed far too poorly to justify its expense, especially relative to say a Corvette. Now, had the production engine developed the 200-plus hp that race/developmental mules developed, things might have been different. But they weren’t. It failed. I understand you like the car; so do I. But it failed.

It doesn’t really matter. If it had been priced at $4500 instead of $5,900 there would have been a back order. It was a limited edition and GM made no money on the car. It was designed to promote hi-performance in the non-hi-performance era and to steel some showroom traffic from the Mustang II. There were 6000 Chevy dealers and 3,508 cars built. 1000 left-over engines were written off for $10,000 apiece. The only winners are the 3508 enthusiasts that went for it. And now they are worth a fortune.

Hi Robert,

“GM made no money on the car…”

My point exactly. That was not intentional – unless intentionally stupid. It was not high-performance, either. Interesting, yes. Potentially a good performer, certainly. But a stock Cosworth is nothing special, especially in view of what the same or less money would have bought circa ’75-76.

These cars are worth a lot of money now. They were practically worthless for many years after their production run ended. They are worth something now because of their low production and the curiosity factor, in the manner of many other such cars. Including the Dodge Daytona/Superbird, Boss 429 and innumerable others that failed when new.

You miss the point of my article, which was not to disparage the car or the concept – but rather the execution.

Worthless? The car was worth $6,000 in 1988 according to Old Cars Weekly. Depreciation in 12 years – $0. You don’t want to spar with me. Want to put your foot in your mouth again?

Spar with you? I’m just pointing out facts, which you appear to have trouble understanding.

$6,000 – in 1988? So, the car was worth significantly less (inflation adjusted) in 1988 than it stickered for new? The car’s original $5,900 MSRP is equivalent to about $13k in 1988 dollars. So if it was “worth” $6k in 1988 dollars it was “worth” less than half what it was worth (cost) new.

Spar with you? It’s like boxing a clam.

Your a dumb ass.

“your (sic) a dumb ass”

Res ipsa loquitur. It speaks for itself.

It did not fail. It passed the EPA test and was the only engine certified in all 50 states. The first Chevrolet to feature electronic fuel injection and the first twin-cam engine built in the USA since the 1938 Dusenburg. Being the second most expensive Chevrolet it wasn’t expected to be a high demand item. What counts is its desirability. Well, it was considered a collectors item when it was new and that my frien makes it a success whether you agree or not.

Oy vey…

A car that didn’t sell well that got cancelled after two years in production failed. Unless you change the definition of “success” to encompass the fact that a car was built and they offloaded a few at a loss.

It passed the EPA test. Certainly. So did the Yugo. It does not mean either was a success.

You like the car; I get that. But you are letting your feelings about it get in the way of the facts about it.

It was considered collectible by those who like them, yes. But it was not especially valuable until many years after the fact. If you know about this car, you know that to be true. It was true of the Dodge Daytona. I know the same about my ’76 Trans-Am. Thirty years ago, it and others of its era were not especially collectible; one could pick up a decent one for $5k or less. Today, it is worth several times that sum because of the passage of time and the increasing interest in cars of that era.

Again, I am not slamming the car – a fact you seem to keep on driving by. I merely point out that it wasn’t successful as a new car. That is a separate question from its success as a collectible car, today.

Did you ever hear of power to weight ratio? The 110 (net) hp Cosworth did 0-60 8.7 seconds (Car & Driver 3/75) The 1974 130-hp pilot car did 0-60 in 7.7 seconds (sar and Driver 1/74), the fastest car they tested that year. The 1977 Monza Spyder 5.0 V8 did 0-60 in 10 seconds. In 1975 the Corvette had 165-hp. Again what the hell are you talking about? Cars those year weren’t fast and they didn’t have a lot of hp but a 2.0 liter Cosworth could keep up with a 5.0 Liter V8. Another reason “its execution” was pretty damn good. And Chevrolet sold the hi-performance parts the engine to give it 200-hp (for racing applications). And the engines were successful in Midget racing. Anything else? Man you’re in the dark.

Yes, Robert – I am familiar with the concept of power-to-weight ratio. The production car (which is all that matters) was still significantly slower than a production Corvette or Trans-Am. And yet it cost as much or more.

And it was still a Vega.

That’s what the hell I’m talking about.

PS: The ’75 Corvette was available with the L-82 350 and 205 hp; the ’75 Trans Am was available with a 200 hp 455. The Cosworth was available with nothing more than its 110 hp four.

I don’t understand your apoplectic insistence that the car wasn’t a failure – when it obviously was. We can debate about why it failed. We can discuss whether it should have succeeded. But to deny it failed is delusional.

Let me tell you something Mr. car guy. The Vega GT outhandled a 73 Corvette on the skidpad. (Road & Track June 1973). In 1972, with Vega sales at nearly 400,000 for the model year and Camaro sales in toilet at 80,000 it was nearly cancelled. So don’t tell me the Vega was insignificant a car. It was the Car of the Year in 71 and beat the Camaro and the Mustang for the award. It was the first “modern” GM car of the 70s designed from the ground up and it was a bargain for the money.

I never said it was “insignificant.” I said it failed. Can you read?

My article treated the car favorably; it noted the significance of the car’s innovative EFI and other features; it mourned what might have been. But it failed – because at the end of the day it was a very expensive, under-performing (for the money) warmed-over Vega.

As opposed to the hugely successful ’77-81 SE Trans-Am.

It didn’t fail. It accomplished its mission. It proved Chevrolet could build a sports sedan every bit as good as a foreign sport sedan. It wasn’t meant to sell. It was meant to showcase the Vega line and Chevrolet hi-performance in the non-performance error. That was its mission and it succeeded. Period.

A “sport sedan“?

The Cosworth was a hatchback coupe. I thought “car enthusiasts” knew that!

It may have handled and even accelerated as well as some contemporary European sporty cars like the BMW 2002 but – unlike the BMW – it was a Vega. That is to say, an economy car with a hopped up drivetrain. Maybe fun to drive – but still a hopped-up economy car. Not a BMW. Which succeeded – because enough people were willing to buy it to make it worth building it.

“It was meant to showcase the Vega line and Chevrolet hi-performance in the non-performance error. ”

Qua Omsa Lagee Wann?

It was not a Vega with a hopped up drivetrain. It was a sports sedan (the Vega handled like a sports car understand? with the powertrain it was a sports sedan. The SCCA classified the Vega Yenko Turbo Stinger (turbo) as a sports car.

with the powertrain it was a sports sedan. The SCCA classified the Vega Yenko Turbo Stinger (turbo) as a sports car.

Maybe you should just stick to Trans Ams.

“It was not a Vega with a hopped up drivetrain. ”

Really? So it wasn’t a Vega with a special engine/transmission/some suspension upgrades and trim? What was the car it was based on, then? Camaro? Chevelle?

” It was a sports sedan (the Vega handled like a sports car understand? with the powertrain it was a sports sedan.”

Is English your second language?

A sedan is by definition a car with four doors. The Cosworth Vega was a two door. Its “handling” is immaterial as regards how many doors it had.

Poor ol’ Clover!

thats right a sports sedan. R&T classified the Vega as a sports sedan believe it or not. The 74 Vega LX was in “Sports sedans VS Sports Cars (all the sports sedans were two door) The Vega went up against the Spitfire (and won). And the hatchback was also considered a sports sedan and C&D had showroon stock sedan races. Vega Pinto Subaru, Colt, etc competed, all called sedans. whether they had a trunk or a hatch.

“thats (sic) right a sports sedan. R&T classified the Vega as a sports sedan believe it or not.”

Sorry, Robert –

I can “classify” myself as short and fat. It does not change the fact that I’m tall and athletic.

A sedan has four doors. As in Sedan de Ville. As opposed to Coupe de Ville, which had two doors.

I’ve had to deal with 30-plus posts from you over an article you admit you’ve not even read. Which you haven’t because you dislike the title.

Ever consider therapy?

“And the engines were successful in Midget racing.”

So were air cooled VW’s, for many, many years.

It worked better for Pontiac? 1971-1977 Chevy Vega 2,010,547 1975-1977 Pontiac Astre 147,773

What the helll are you talking about?

Robert,

What I’m “talking about” is that the Cosworth Vega sold very poorly; that the black and gold paint scheme that it featured (and debuted) didn’t help it sell – as it did help the hugely popular black and gold SE Trans-Ams of ’77-81, which made that look iconic.

Very few people even know what a Cosworth Vega is – or have even seen one.

Everyone knows what a Trans-Am is and recognizes the “Smokey and the Bandit” cars.

Enough people know about it. Don’t kid yourself. Yours isn’t the first retrospective article. Here have been many in 40 years including my car in Motor Trend Classic and Hemmings Classic Car. They didn’t think it was doomed. They praise it because they are true car enthusiasts not critics.

https://www.motortrend.com/reviews/1976-chevrolet-cosworth-vega-vs-mercury-capri-ii/

https://www.hemmings.com/stories/article/chevrolutionary-1973-chevrolet-vega-gt-millionth-edition-1976-chevrolet-cosworth-vega

The old ad hominem… I’m not a “true car enthusiast.”

I’m also not tall.

What others write isn’t necessarily what’s true. Was the car interesting? Innovative? Yes, certainly. But it failed… an obvious fact that for some bizarre reason I cannot fathom you refuse to acknowledge. You’re entitled to your opinion but if you’re not open to facts there’s nothing I can do to change it.

Your article fails before the first sentence. Motor Trend Classic and Hemmings Classic Car. Facts? You probably got some from my Chevy Vega Wiki or Wikipedia which I wrote years ago. Not opinion, just the facts. I let my readers draw there own opinions.

https://chevyvega.fandom.com/wiki/Chevrolet_Cosworth_Vega

Robert,

My article points out that the car failed – which is indisputable based on the weak sales and abbreviated production run. Those are facts. What Hemmings and Motor Trend writers – and you (or I) – think about the car’s merits is entirely beside the point. It didn’t sell; GM had to practically give away the relative handful it made; then it pulled the plug. That is a fail. Unless you think a car company defines success as building cars that don’t make money, which it ends up offloading at heavy discounts and cancelling quickly, so as to staunch the losses.

By that definition, the Pontiac Aztek, Chevy SSR and Lincoln Blackwood were “successful,” too.

You are obviously emotionally invested in the car, which is fine – I love my Trans-Am, too. But the difference between us is you’re blinded to the fact of the car’s failure on the showroom floor – as opposed to its status as a collectible curiosity today.

Smokey and the Bandit…1977. Well The Black and gold color scheme John DeLorean chose for the Cosworth Vega in 1974 predates the T/A. So what Pontiac was blessed to get some publicity for the overweight, emissions choked Firebird with the screaming chicken graphics..so 70s. Was Burt your hero?

My point – which continues to escape you – is the fact that the ’77-81 SE Trans-Ams (and the non-SE Trans-Ams of that era) were a massive success for Pontiac. Indisputable. That the Cosworth had the black and gold paint scheme first doesn’t bear on it. Or change the fact that the Cosworth was not a success. You continue to be blinded by your obvious affection for the car. It manifests in your derogatory comments about successful cars, like the Trans-Ams of the same era.

PS: All the cars of the period were “emissions choked” – including the Cosworth. It is why the production car eneded up with a 110 hp version of the potentially brilliant engine. I assumed a “car enthusiast” would be aware of this.

HP means nothing. I said it did 0-60 in 8.7 seconds which was faster than a prototype with a different EFI set up and 20 more hp.

Robert,

However quick it was (and it wasn’t, very) it wasn’t enough to sell. That is the point you obtusely continue to miss!

The Cosworth didn’t half the emissions devises in that Trans Am. It was the cleanest running engine in 75 by the way. Partially due to the 16 valves per cylinder. No air pump. Only a pulse air system. By the way, C&D said it was the most sophisticated engine Detroit ever made. Don’t know if its in your article cause I didn’t read it because of that stupid title.

“The Cosworth didn’t half the emissions devises in that Trans Am.”

I am not familiar with emissions “devises.” Nor what “half(ing)” them means. Is that like calving? Perhaps you will explain? As far as emissions devices, the ’76 Trans-Am had the following: One catalytic converter; one EGR valve; a vapor recovery system. Plus a few vacuum hoses to the carb and so on. No air pump on the 400 or 455 V8.

But – again – whether the Trans-Am’s emissions were lower or higher or the car’s engine more or less powerful/sophisticated is beside the point. The TA was a hot seller; it made money. The Cosworth was a boat anchor tied around dealer’s necks. It lost GM money. It failed.

Poor ol’ Clover!

I purchased my first Vega (a 1973 sky blue auto sedan) from my sister in the early 80’s. It was leaking oil out of the rear main seal so she wanted to get rid of it. I put a new seal in it and ran it for a few years…until it was involved in an accident.

In the late 80’s, I had seen a classified for a 1975 hatchback with a standard trans for $200! The owner stated that it needed transmission work. With the clutch engaged, there was no movement…he panicked, and somehow had locked up the shift linkage into reverse. I went to look at it…and told him that I would let him know, then, I decided that I probably did not need another car project at that time.

I called him the next day and offered him $100 for the Vega. I figured that he would say “no”, and that would be the end of it. Much to my surprise, He stated that, at the breakfast table that am, he was talking about me with the family…and they had decided that if I called back, they were going to sell it to me for $100! Gulp…It was meant to be!

My brother and I took a run over one afternoon and freed up the linkage. Then we attached a thick rope to the lime green Vega…and proceeded to tow it about 15 miles to my house (Those were the days…today I would probably be thrown in jail, and the Vega confiscated).

I started it up the next day and he was right…no movement with the clutch released. On a whim, I jacked it up and adjusted the clutch. I dropped it down and then proceeded to drive it away!

I drove it for 2 years like that, before biting the bullet and installing a new clutch assembly. Inexplicably, it ran quite well. If i am not mistaken, this engine had the steel sleeve for the pistons, which made a big difference. I ran it for a few more years, until it rusted out and would no longer pass inspection.

The Vegas always had an odd exhaust sound while accelerating…similar to a cow ‘MOOING”!

Good Times!

Well, according to Robert and his posts…I guess that my 1975 Vega did not actually have a steel sleeve for the pistons…unless it was a re-manufactured engine.

I was pretty happy with my Vegas after doing some work on them. I had 2 ’75 coupes and 2 ’75 wagons. I bought them in the early ’80s, cheap. One of each to drive, one of each for parts. Both “drivers” were “high-end” Vegas. As I recall, badged Spyder. Sure was handy to build an engine or transmission out of the parts car and then in a couple hours have your driver up and running on the new one.

We lived in the boonies so they were economical go-to-work or go-shopping cars. Actually fun to drive when I was done with some engine work.

On problem I have not seen elsewhere is that it was possible, after wear, to get the car in two gears at one and lock up the transmission. Always with the car standing still, thankfully, when shifting to low from second or third at a stop light. Each car had a blanket in it and my wife and daughters were shown how to slide in under the driver’s side and move the shift levers into neutral. I found that the problem was that the spring-washers in the shift mechanism would wear/fatigue enough that two forks of the shifter would be able to move together. Easy enough to fix, but a real nuisance until I finally diagnosed the cause.

I lost timing belts on both of them. Both were tossed at engine start, one in our driveway, one at work. I called my wife on the second one, had her get a belt, and made the repair in the parking lot at TRW in Huntsville.

Both engines had to be rebuilt at about 100,000. On the coupe, the death came because one July I packed up the family and we went on a tour around the south for a week. Two adults, two teens and all their gear, A/C running full blast. At the time we left, it was burning about a quart every 1000. By the time we got home it was burning a quart every 100. Heat was really that engine’s enemy. But even the low-water warning signal the cars carried by then didn’t help since the radiator was insufficient to handle that kind of service.

When I rebuilt, I outfitted the coupe had a Weber carb (the price of the Lira vs Dollar kept me from buying one for the wagon when I rebuilt it about a year later). Both had headers, and a cam. I had the blocks sleeved and, by then, the slit to better move water in the head had already been baked-in by Chevy. Most machine shops knew how handle Vega engines, including milling the slit on older heads. I sold the wagon to a friend when we left the area and he put nearly 150,000 on the rebuild before he got rid of it.

I advertised the two parts cars and a salvage yard came to get them. They told me the only thing they really wanted were the forged aluminum bumpers and the drivetrain. All for melt-down. There was little call for replacement parts for Vegas in 1992.

The Vega had one of the worst rust problems I have ever seen on any American car, but many 1970s GM cars and light trucks had the same issue. There are stories about leftover new Chevrolet Impalas and pickups starting to rust on dealers’ lots. My dad’s 1976 GMC Suburban, bought new, had severe roof rust within three years. Repainting didn’t stop it.

The reason for the rust is widely misunderstood. It had nothing to do with poor rustproofing or water being trapped anywhere. No, these cars were doomed to rust because GM began using recycled steel around 1970 to save money. That steel was not heated enough to get rid of rust before being used in new body panels, so microscopic bits of rust were trapped inside the new parts.

And you know the saying: rust never sleeps. The panels would rot away from within and nothing would stop it. Nothing. The fender or whatever would appear to have rusted from the back side (inside) as is common with older cars. Not so. It rusted from within itself, and the process started as soon as the panel was made. That’s why the rust appeared so quickly. The only cure was replacement metal or fiberglass panels. For roofs, pillars, and floorpans, that isn’t economical for most cars.

GM was still doing that long after the 1970s. Chevrolet and GMC pickups built into the ’00s have real problems with rocker-panel and cab corner rust. There’s no excuse for it.

By comparison with the Vega, the much maligned Ford Pinto was actually a much better car, excerpt for the gas tank problem. The Pinto drivetrain was generally solid and the body was not particularly rustprone. Well into the 1990s, long after Vegas disappeared, I would still see the occasional Pinto on the road.

I can’t imagine given the history that the Cosworth Vega was any less rustprone than the standard Vega. That alone ensures few survivors. Putting the Cosworth engine in that car brings to mind the old adage about lipstick and a pig.

Amen, EK –

I’ve defended the Pinto for years. It was a perfectly sound car for its intended purpose. Even the gas tank (fuel filler) issue was a minor design defect that presented a very low overall risk. The car had to be hit just right for a fire to start – and very few did, relative to number of Pintos made.

My first car was a ’73 Vega station wagon that I named “the raped ape”. It was invincible & had plenty of room for my work clothes & boots; fishing rods & tackle; you name it. Very few of my classmates would ride with me. The notable exception loved to throw the emergency brake handle while we were flying down windy dirt roads. For a dumbass teen it was the perfect POS -underpowered, bulky, not particularly good turning radius, and from my parents’ it standpoint guaranteed I’d never get laid. That said a couple years ago I saw a Vega wagon make respectable times at the local dragway. I felt completely vindicated.

Hi Mike,

There is nothing wrong with a Vega that a small block V8 can’t cure! Great memories re the emergency brake pull-up trick. I have them, too!

A V8 is so heavy it would have forced the car to understeer. Understeer is not a concern if all one is doing is racing between stop lights. But if that’s the case, then eliminate the lights, turn signals, side markers, radio/speakers, P/S, P/B, A/C, lighter/ashtrays, roll down side windows, etc. Straight line acceleration is not a feature to design for if one is selling to the public. A V8/V6 does not solve problems, it creates them by putting too much weight up front. If you want an amusement park ride, then by all means, put in a V8/V6. BMW didn’t put V8’s in the 2002 because they were not selling cars to pimply-faced teenagers. I see no reason why Chevy should have done it to the Vega, even for less than $3000. No one designs mass produced cars for teenagers because they don’t sell. Daddy has to pay the bill, and that is not going to happen on a mass scale.

Hi Kevin,

I never criticized the Cosworth for not having a V8; I criticized it for being a too-expensive Vega! The sad thing about this car is it was a showcase of engineering innovation that ended up being badly compromised by government regs such that it offered too little in the way of power/performance (110 hp; 0-60 in about 8 seconds) for the money, which caused it to sell poorly – which led to its cancellation after just two years on the market.

“There is nothing wrong with a Vega that a small block V8 can’t cure!”

And I responded to your suggestion to solve some sort of mythical problem with a Vega that a V8 could cure, not with the Cosworth.

But lets get to the Cosworth high price. You suggest a solution to a pricing problem by installing a solution that disrupts the neutral handling. Who would buy a stock V8 Vega (no longer a Cosworth) for racing that can’t be held on the road because of a horrible understeer problem that you have now introduced a major problem that undermines the entire purpose of a Vega racer, just to solve your pricing problem? Now you have a much smaller market despite having lowered the price and failing to impact the Vega image. And you have not introduced advanced technology to which to accustom the market for future models.

Words mean something. Suggesting a V8 block/head, instead of a EFI, DOHC head on a standard Vega block would put Chevy further in a hole on the Vega. Replacing the Cosworth price with a Camaro price to compete against the Camaro would have done nothing to improve over Cosworth sales, and would have drawn more than a few low-end buyers away from the Camaro, which was already in trouble in the early 70’s.

With a stock V8 Vega, you have failed on 2 fronts just to replace units sold as Cosworth for a lower price. BTW, Chevy did build at least one V8 Vega prototype, and determined it was a loser. The 2 failures are loss of sales to technology buffs who want an advanced car, in this case, EFI and DOHC. Second, you take customers away from Camaro sales that had a higher per unit profit. Its all about how much money can be made.

In the article, Kevin…

Christ on a cupcake.

I suggested no such thing… in the article; the quip you copied was an off-the-cuff and entirely facetious comment in reply to someone else’s comment about Vegas generally. I’m well-aware of what the weight of a V8 on the nose of a car never designed for it would do to its balance and handling. Also that the Cosworth was meant to be a very different kind of car than a V8 muscle car.

The time I spend arguing with people over these non sequiturs … it’s exhausting.

Ha!

Like fighting with: wavy wire mesh, sideways going screws, warped & split boards, and dried in place layered gravel embedded in hard packed dirt?

I guess you’ll learn not to make those facetious comments. It takes some longer than others. There is a time and place for it, this is not one of them. I’m an engineer, and I learned that back on day 1 and require both students and staff what professional communication is. Of course, you may not view this as professional. If so, then I’ll take everything here for what its worth.

Oh for Christ’s sake, Kevin –

No, I will not “learn to not make those facetious comments.” Get a sense of humor. And stop berating people for having one. As far as “professional communication,” I daresay I have established my bona fides in that regard far more so than you have.

Kevin,

Even with all of its “advanced” technology, the Cosworth production engine only managed 110 hp. To put that in some context, the same-era Kawasaki Z1900’s 900 cc DOHC four, with four carburetors and no computers, developed 79 horsepower from less than half the displacement.

I own one of these, by the way – and with a simple increase in compression from the stock 8.2:1 to 10.75:1 and some minor tuning the Kaw 900 develops more than 100 horsepower.

On the other end of the spectrum, a 1975 Corvette’s optional L-82 350 (5.7 liter) V8 developed 205 horsepower, roughly twice the Cosworth’s horsepower (and far more torque) from a bit shy of three times the displacement, but (unlike the Cosworth) without any of the technological advantages and still delivering better performance, despite being severely gimped by such things as a highly restrictive exhaust system, mild camshaft and tuning designed to decrease emissions, which decreased horsepower considerably.

The Cosworth just didn’t deliver – for the money. Who would pay as much as a Corvette cost to drive a car that was not even as quick as a Trans-Am (which cost a lot less than a Corvette)?

The Cosworth engine was rated at 290 HP before it was transported to the US for scrutiny by the EPA. The story if EPA certification for the 1974 model year was nothing short of a comedy of errors. Hence, the Cosworth didn’t debut until 1975. But at 290 HP, I think the sort of buyer that could afford a $6,000 advanced car would not have brains enough to keep a 290 HP car on the road. So the EPA was saving lives in a more direct manner. They dumbed the engine down for obtuse Americans with $6,000 of disposable income. As for Cosworth Engineering, they knew what they were doing to squeeze 290 HP out of the block. They didn’t get a reputation as a premier F1 engine designer based on stock engine sales or retrospective auto critiques.

Kevin, you stated

“No one designs mass produced cars for teenagers because they don’t sell.”

Really? There was a Pontiac that made it’s debut in 1964, three letters I believe. They sold almost 30,000 that year. Guess who they marketed the car to?

Oh!, that’s right! The YOUTH market!

I agree Eric, oy vey!

Amen, Douglas!

Kevin spent a lot of time “correcting” me for a statement I made in passing, in obvious jest, that was peripheral to the article and the sentiments expressed herein. Meanwhile, I’ve received at least 40 abusive texts from a guy outraged by the title of my article, who confesses he hasn’t even read it.

And they ask me why I drink…

Eric, the guy sent you 40 abusive texts? Not surprised, that’s what he does. He sent me one at 4:30am, waking me up, a couple days ago because I, and virtually everybody else who commented had the audacity to disagree with a post he made on a Facebook Vega forum. Then after I asked him to stop he sent me 3 more. This is at 4:30am mind you. He then kicked out a few members from the group who had disagreed with him. No opinions besides his or those who agree with him are tolerated in that group because it’s “his group”. He then deleted the post of course. One of the members named Shane he kicked out because the guy called him an idiot for being so closed minded and not allowing any differing opinions. Said it was because of the “idiot “ comment yet the same guy has no qualms calling you the same thing here.

Hi John,

Wow. A true Freak. These pop up occasionally. I try to be civil but they often make it impossible. The crazy thing is I share the guy’s affection for the car. But he is all riled up because of the title of my article about the car.

“They sold almost 30,000 that year. ” Note: reference to another Delorean project, the GTO. “The Vega was assigned to Chevrolet by corporate management, specifically by GM president Ed Cole, just weeks before DeLorean’s 1969 arrival as Chevrolet division’s general manager.” And that’s “a whole ‘nuther article” including Vega assembly line sabotage.

You’re making my case. 30,000 is a failure even by Vega standards. If Chevy had such low standards for the Vega, then why are you citing even lower standards to make your point? You’re using statistics that prove my point, not yours. At least the Vega Cosworth advanced expectations for higher standards even at only 3,508 production pre-dating the Japanese designs by a decade. Can’t say that about the GTO. The muscle car era ended in 1973 with the oil embargo. Aluminum blocked, EFI, DOHC is still a marketing rage even after the way-ahead-of-the-curve 1975 Cosworth.

When Camaros reached down to 80,000 units in 1972 they were going to be put on the block, and that was a signature marque. The Vega production line in Lordstown made 30,000 Vega units in 2 weeks during their production peaks. Why would Pontiac build and maintain an entire production facility for only 30,000 units in a year? Oh yeah, so pimply-faced kids could have a lunch box to drive to high school. Right! No wonder Pontiac no longer exists, and I think accepting buyout money from the federal government was a damn shame instead of letting the market make the decision to close the brand.

Vegas never got close to having a year so poor as 30,000 units. Even the last year as production was being cut back the numbers were more than twice that at 77,000. The decision to close the marque was made when they were making 160,000 units in 1976. That’s the Vega standard. Get it? 30,000 with a “go” is less than 160,000 with a “no go.”

The truth is, it had nothing to do with production numbers. All of the H-bodies, including the Monza variant, were on their way out by the end of the 1970’s due to be replaced by the 2nd Gen X-body front wheel drive, considered to be the future. The decision to close the Vega line was pre-ordained long before the decision to shut down Vega production was made as development time for the 2nd Gen X-body (on the market by 1979) took several years.

There were 2,000,000 Vegas made from 1971-77. I like GTO’s and am looking for one now. Where can I get a millionth edition? Oh yes, there isn’t one. I guess I’ll have to settle for a millionth edition 1973 Vega instead.

Now, back to the original proposition, was the Cosworth over-priced? My answer is, well, I thought so. But it sold because there is always a fraction of the market willing to pay prices that cause us regular people to gag. But the same question can be asked of the super-car prices (the Cosworth was not a super-car, but the Cosworth did not have a super-car price). Yes, there is a market. Was the Cosworth a success? Sales figures are not the measure of success. Before the success question can be answered, the basis of the definition of success has to be established. That is done by answering the question, “What were Chevy’s objectives with the Cosworth?” Only then you can compare the outcome with the intent. Did the Cosworth boost the image of the Vega? Did EDI, DOHC, and aluminum engines become the manufacturing standard? I’ll let the reader do the research instead of force feeding them the answer.

Hi Kevin,

By circa ’77-79, Pontiac was selling in excess of a quarter million Firebirds annually – about half of them Trans-Ams. Pontiac was hugely successful – when it still sold Pontiacs, rather than rebranded Chevys.

As far as EFI:

The chief advantage is tune-ability for emissions compliance, not performance. A carbureted engine can make as much or more horsepower, all else being equal. And some of the better carbs – like the Rochester Quadrajet – can deliver cold start performance and throttle response nearly as good as EFI, without the complexity or the cost.

DOHC has its merits, too – but keep in mind that current OHV (and two valve) V8s such as made by GM and Mopar are developing 400-700 horsepower in a simpler, less expensive, smaller package with daily driver manners and reliability.

I own a bike – 1983 Honda GL650 – with a pushrod/OHV twin that can spin to 10,000 RPM. Just fyi.

BTW, the prototype Cosworth engines were rated at nearly 300 HP. That was before the EPA got their hands on the engine and it was “dumbed down” to 110 HP for the American market. I frankly don’t think the American consumer paying $6,000 for a 300 HP car in the 1975 could handle the car on the road, but my opinion on that is irrelevant. Huge difference between the capability of the engine and what the EPA forced on Chevy. And it might be mentioned, Cosworth Engineering was a world renowned F1 engine designer. So the Cosworth at nearly $6,000 had the potential for being one of the outstanding cars of the century. It was not GM’s fault or Chevy’s fault that the EPA gutted EVERY car allowed in the US market. Put the blame right where it belongs, on the EPA. Or, because it is easier for lazy slavers, should we just blame Trump for the EPA not allowing the Mercedes Benz 500SL to be imported into this country for dealership sale during the 70’s? (They were imported through private purchases in Europe).

Hi Kevin,

Yes – and prototype 1973 SD-455 Trans-Ams were running 11s through the quarter mile. It means nothing as regards what was actually offered for sale.

I agree with you as regards what the EPA did. But the fact remains that the car as produced was under-powered and over-priced and (worse) it was a Vega. At least when you bought an under-powered, emissions-gimped ’75-’76 Corvette you were driving a Corvette. It being under-powered as it came could be rectified – easily and inexpensively.

But how do you rectify a Vega?

The engine deserved better.

Sounds to me like you’re critiquing the Vega, not the Cosworth. My opinion, but I don’t believe the Cosworth was meant to be a solution to the Vega problem. I think it was a suggestion for future models, not a solution for the Vega because the H-body was slated to be terminated by the end of the decade. Of course, I agree with most of your statements. I’m not saying you are working from an unsubstantiated platform. And I see that you agree with many of my statements. It’s the subtle differences in perspective where the disconnect happens. No credible perspective can ignore the problems that occurred along the way. I acknowledge the factual problems (there are many fantasy-based problems dredged up by emotional biases), and I’m sure Robert above acknowledges the problems also. But failing to place the Vega and Cosworth in context is a major flaw in the vast majority of critiques I have read. And with that said, you can look at that 2 ways: (1) Everyone agrees so it must be true, or (2) the retrospective critique community is an echo chamber and nothing is worth reading anymore because we’ve heard it all before. Both perspectives apply at the same time. Its a double-edged sword. Placing the Vega or Cosworth in context would be a novel approach to retrospective critiques. And we’ve already started to do that in this comment forum, you included, comparing to specific details of Trans Am, BMW 2002, GTO, etc. All of that needs to be considered in a Vega or Cosworth critique because it tells the background story of how and why decisions were made. It is easy for us to sit in our cushy offices in 2021 and pass judgements on people in the pressure cooker in the 1970’s. But it does nothing to layout how and why those decisions were made unless the background story is included and considered.

Hi Kevin,

It’s not so much a criticism as analysis. I actually like the Cosworth Vega. I like quirky cars. I like interesting cars – and the Cosworth was both. But it was a Vega. And the Vega was designed to be a transportation appliance economy car. There is nothing wrong with that, as such. But it becomes a problem when you try to sell it as something exotic – as opposed to something with an exotic engine.

Circling back… the article (and book) is fundamentally about cars that failed. The Cosworth Vega failed. It didn’t sell well; it was quickly forgotten. It had nothing even approaching the impact of the Pontiac Trans-Am. And I refer to the ordinary, regular production version thereof. The specialty iterations such as the ’73-’74 SD-455 are legendary and among the most collectible classic cars extant.

Part of the reason for that being their exotic engines, of course. But also in no small measure because the car, itself, was hugely appealing to millions of people.

The Cosworth Vega and the Vega itself are just another coulda-shoulda-woulda product from General Motors. A good idea with a flawed execution due to the agendas within GM that lead to market failure.

Even if we put the problems with Vega as car aside, for the sake of argument, GM was never going to put out Vega that out performed Camaro, Corvette, etc for a low low price. Sorry. It was going to fail because corporate marketing doesn’t allow for the tiers to be interrupted that way. If they can’t kill it outright they will castrate it or price it higher than people are willing to pay.

We are talking about an era where over at Ford they wouldn’t even put a tach or a 4speed in Maverick for fear it would take away sales from Mustang or Mustang ii. BTW performance options were available on Mavericks built and sold in Brazil, because the Mustang wasn’t.

This is how the big three did their marketing. Look at what GM corporate did to the Fiero.

Things like the Cosworth Vega were doomed for a variety factors including the era in which the decisions were made and the corporate conditions there of.